Carolyn Lazard’s inaugural solo institutional show, Long Take at ICA Philadelphia, embarks us on the artist’s intellectual journey with the methodologies of access. Showcased at the center of the room, a versatile installation named Leans, Reverses (2022) anchors the exhibition. It is made of three dark television monitors displaying a textual description of a dance performance in white writing. In addition to rendering the performance accessible for blind or low-vision audiences, the eighteen-minutes-long moving text image (which is also broadcast through speakers) challenges us to not think of sight as the primary way to experience a dance show.

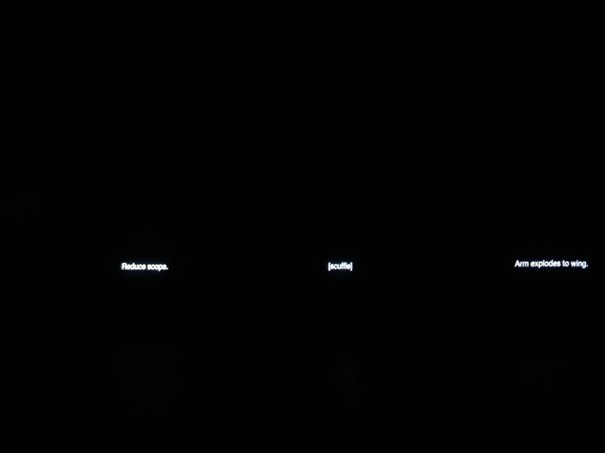

Leans, Reverses (2022) pays tribute to Lazard’s sculptural and collaborative artistic approach. Moving one’s gaze from left to right, it is possible to observe the stepwise construction of the three-channel video. The first screen unveils the score of the dance composition, which Lazard wrote for dancer and choreographer Jerron Herman. In the middle is the caption of the dancer’s own interpretation of the score, featuring visual onomatopoeias mimicking the sounds of the lavalier microphones placed all over its body. Lastly, the far-right monitor displays an audio description of the performance written with poet and artist Joselia Rebekah Hughes. This collaborative endeavor with other artists in the disability arts community serves to redirect the emphasis of accessibility away from an individual concern.

The exhibition ultimately presents itself most convincingly as an immersive environment. Upon entering the room, the audience is invited to take a seat on a bench facing the display of screens. It is one of three interspersed ‘Institutional Seats’. Lazard sourced these benches from the ICA itself and crafted them to provide a level of confort not usually found in arts venues. Surround Sound (2022), the gallery intervention, allows the visitor to walk under dispersed spotlights that establish a scenic atmosphere. The black walls adorned with Marley floor—a specialised vinyl flooring commonly used in dance studios—evoke a site between rehearsal space and stage, where the visitor may alternatively identify as a spectator or as a protagonist.

In a holistic approach, the artist meticulously considers not only whether visitors can experience the gallery, but also how they can do so, and for what duration. Many of Lazard’s artworks have explored the question of time. Prescription drugs act as a skewed clock as Lazard meticulously replenishes colored boxes in Crip Time (2018). This artwork calls into question the productivity paradigm of capitalist society, which requires us to remain productive, even in the face of illness or exhaustion. On the other hand, Long Take moves away from the historical association of modern dance with fugitivity and impermanence. Following dance for camera, a movement popular in the 1960s which sought to reimagine how choreography might prioritise the cinematic frame, the exhibition’s title, a nod to a type of camera shot praised by the artist, suggests the possibility to extend the temporal boundaries of a dance performance. Lazard also affirms a different formal radicality, proposing that dance can be experienced not only visually but can be heard or felt.

Increasing accessibility in the arts appears as a delicate balancing act between transcription, translation, and creation. To Lazard’s own acknowledgement, relegating vision to the status of mere faculty inevitably casts a veil of opacity around the potential to understand the artistic enactment. Importantly, the premise that the opacity of an artwork holds a sacred quality constitutes a fundamental aspect of their artistic approach. In their words, “Opacity is a way of retaining that which is irreducible about ourselves, that which cannot be imaged, but might be heard or felt, or transmitted by some other means.” Yet, one reviewer’s remark that “it’s ironic that grasping Lazard’s concept may be the hardest part of accessing this piece” suggests that Lazard’s theoretical framework may have been overshadowed by their emphasis on the practical aspects of translation. This sentiment was echoed by a conversation I overheard when exiting the exhibit, with viewers seemingly leaving the room feeling perplexed. While Long Take effectively demonstrates that enhancing accessibility in the arts does not necessitate a reduction in complexity, it is regrettable that some of the important messages conveyed in the artist’s deliberate focus on reformulating artworks rather than confining them to transcription, are, quite literally, lost in translation.

Instead of providing definitive answers, the exhibit stimulates a dialogue on the methods of enhancing accessibility in the arts and their inherent limitations. They pose questions such as: Can dance film exist without its visual element? Can dance be conveyed through sensory modalities other than sight? In this way, the show serves not only as a radical thought experiment inspired by dance for camera but also as a literal embodiment of the principles outlined in Lazard’s manual, Accessibility in the Arts: A promise and a practice (2019). This essential how-to-guide geared towards small-scale arts non-profits and their public delves into how organisations can actively dismantle ableism and create truly inclusive spaces.

In the same vein, Long Take offers seemingly simple, and yet underexplored, solutions to the barriers which hinder access to cultural events for disabled people. As an underlying theme, it suggests that the artwork and the experience hold equal significance, viewing them as two sides of the same coin.

Laisser un commentaire